- Home

- Richard Farrell

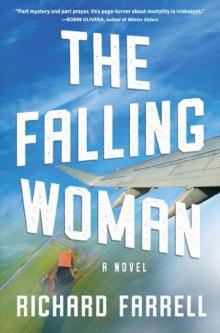

The Falling Woman: A Novel

The Falling Woman: A Novel Read online

The

Falling

Woman

a novel

Richard Farrell

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2020

And now will drop in SOON now will drop

In like this the greatest thing that ever came to Kansas down from all

Heights all levels of American breath

—James L. Dickey, from “Falling”

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

NTSB: Witness Document 1.18.4.3

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

NTSB: Witness Document 1.18.4.4

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

NTSB: Witness Document 1.18.4.5

About the Author

Prologue

. . . and then my seat gives way and black sky siphons me through a gaping hole in the fuselage, my body aspirating through the suddenly ruptured coach-class ceiling like a lottery ball in a pneumatic tube. Jagged teeth in the disintegrating cabin tear at the fingers on my left hand. Shattering aluminum nearly decapitates me. And suddenly, I’m outside. I’m outside. These are the words that flash as my body, still strapped to my seat, zooms past the tail. I’m outside. Lights flash by. I’m outside. I close my eyes. I tuck my chin to my chest. My body somersaults.

And then I’m alone.

Falling through the night sky.

I fall toward humid cornfields, toward silos, barns, and bridges. I fall toward varsity quarterbacks dreaming of glory, toward farm girls with pet rabbits, toward meth heads riding the rails, toward retired veterans, librarians, lunch ladies, and lucid dreamers.

Down and down I go, accelerating earthward for nine seconds before I reach terminal velocity, a point at which the sensation of falling ceases. Freezing air riffles past. Sprays of rain and plinks of hail punch and jab, scratching my face. In my mind, I see my daughters, babies again, crawling along the kitchen floor, two perfect angels, reaching for me, and the pressure of their yearning, memories so deep and physical that, for a moment, I forget what’s happening. But then the rush of air, and the rain and hail, become painful. The temperature warms as I drop. Humidity increases, the dewy sweetness of loamy farm smells rising up, my body spiraling, still strapped to that seat, twirling and twirling like a seedpod in a late summer breeze. I open my eyes. Lightning flashes in clouds. Then a split second later, I spot the flaming comet tail of the plane, my plane, disintegrating, its aerodynamic fragments still flying away from me, shedding pieces of itself. I think of Peter, Paul and Mary singing that song my mother loved—“Leaving on a Jet Plane”—until I pass through the densest parts of the storm and the plane disappears for good. And I’m still falling. Instinctually, I grab the side of my seat with my undamaged hand. I grip it with fury, with everything I have left. Streaming blood coats my face, stinging my eyes. My blood tastes like a cocktail of copper pennies and Communion wafers. Oh, if ever there were a time to still believe in God. My one remaining shoe rips off. Then my shirt flutters over my face and disappears into the night. A moment later, my bra peels away and then my underwear goes. I was always so modest growing up, always afraid to be seen. Bloodied and naked now, I begin to scream, only to stop in terror when I can’t hear the sound of my own shrieking. How can I know that I’m outracing my voice? I fall and fall. And when it seems impossible to continue, when it seems that I’m trapped in a nightmare from which I will surely soon awaken, I begin to count. I count, slowly, in my head—one, two, three, four, five. I count all the way to fifty-seven. I’m still falling.

More than anything, I just want to reach the end, no matter what that means.

1

U.S. House of Representatives Panel Investigating Pointer Airlines Flight 795 (First Session):

“Could you state your name for the record?”

“My name is Charles Radford.”

“And your involvement with the investigation of Pointer 795?”

“I was an investigator with the National Transportation Safety Board.”

“In fact, sir, you were the lead investigator for the survival factors working group. Isn’t that correct?”

How many times, he thinks, do I need to answer that question this week?

He reaches for the glass of water in front of him and glances down at his notes. Sixteen congressmen stare back at him from the stage. Behind them, pages, interns, and lackeys tussle with papers and phones. For the third day in a row, Radford has crossed the National Mall, checked his reports, sworn the oath, and sat stock-still in uncomfortable chairs waiting to testify. Three days of note scribbling, of listening to others, sidebars with attorneys, frantic calls home, and second-guessing. The entire Go Team—including Lucy Masterson, Shep Ellsworth, even Ulrich and the director herself, Carol Wilson—have gone before him. Now it is his turn. At his back, cameras record every move, every word.

“Need we remind you that almost twelve months ago, a commercial airliner exploded over south-central Kansas? Need we remind you that 123 people died, or at least that was the initial assumption from your agency? Need we remind you that this country has waited for a definitive answer? Terrorism, a bomb, a missile, a meteor, a short circuit in the plane’s wiring, a lightning strike?”

“No,” Radford says. “I’m well aware of what happened to Pointer 795. I’ve spent countless hours sifting through debris fields, maintenance records, and logbooks. I’ve waded into ponds to extract bodies. I’ve interviewed orphans and widows. I’d say I’m well acquainted.”

“But you have no answers.”

“I don’t deal in answers,” Radford says. “My job was to ask the right questions.”

“For the record, sir, how many aircraft accidents have you investigated in your career?”

Radford shrugs. He knows the number but refuses to make this any easier.

“Would you classify the investigation of Pointer 795 as standard, as routine?”

“In the beginning,” he says, “there was only havoc, devastation, and raw loss. Any solution seemed impossible. I needed to figure out which questions to ask.”

“So, is that a yes, sir?”

“Events gathered in reverse,” he says. “A chain of a thousand invisible mistakes had to be pumped back through time. Complex decisions teased apart, examined, challenged, abandoned, and reexamined. A forgotten switch closed. A valve not pressurized. A checklist item skipped. It’s always about asking the right questions.”

He knows he is rambling. Is he losing his grip on reality? He reaches again for the water and tries to organize his thoughts. So many others have sat here before him, men and women in positions of great power as well as the meek like him. Even this conference room, located in the bowels of the Rayburn House Off

ice Building, imposes its will, with its bone-white ceiling, its sticky chairs and sweating pitchers of water. On the wall is a framed painting of the Great Seal of the United States. The American eagle—wings outstretched, talons clutching thirteen arrows in the left, an olive branch in the right—stares down at him along with the congressmen.

“Mr. Radford, what we’re concerned about is where the investigation deviated from protocol. Why were you reassigned?”

“Sequences accrued,” he says.

He knows they have no right to be doing this, no reason to challenge his expertise. He knows he has done nothing wrong. He simply followed the evidence. About the rest, about the way the rest unfolded, about that he has no regrets. The contradictions, the impossible contradictions of this investigation, these were not his fault.

“Sir, the investigation quickly went off track. Why did this happen?”

“The job demands you filter out assumptions,” he says. “You gather the millions of scattered pieces and reassemble fragments into questions. If you ask the right questions, the rest will follow. To get from chaos to order, you have to trust cause and effect. This is how the work begins. Hours and days and weeks pass. Some pieces lost forever. The wreckage must be rebuilt, one rivet at a time.”

He pauses and looks up at the eagle on the wall.

“Three babies were aboard that flight,” he says. “Each body deserved a name, a next of kin to grieve it. That was my primary responsibility.”

“Let’s concentrate on the bodies. How many had you identified before you were reassigned?”

Why does he still hate uncertainty? Why is it still so hard to talk about? These congressmen don’t understand his work.

“The short history of human aviation,” he says, “is barely more than a century old. Flying used to be incredibly dangerous.”

“Mr. Radford, we’d like to stay on track.”

“You demand answers,” he says. “You expect nothing to ever go wrong. But your need for certainty is an illusion. You take it for granted because you fail to see the miracles anymore.”

He’s trying to explain why the sky is inside him. If they mined down into his soul, they would find wings. The sky runs through him, into places of himself he still hasn’t mapped. A calling, perhaps, the way a priest is called, or like the passion of great lovers. Since the winter day when two brothers from Ohio closed their bicycle shop and fashioned together a rickety kite frame made from spruce wood and Roebling wire rope, thousands of others have been likewise called, and followed a path into the air. A coin flip and a steady Atlantic breeze changed history. What followed was more than just another invention. The airplane expanded human imagination, took us into places that we’d only dreamed about since we first stood erect and told stories. Radford has been more faithful to the sky than to anyone or anything he’s ever loved. He has never doubted this love, not once, not since he was ten years old. But what has he been chasing all these years? For the first time in his life, he’s not sure.

“Sir, refusal to answer this committee is serious violation of federal law.”

“What a crock of shit.”

“What was that, sir?”

“Do any of you,” Radford says, “understand the first thing about flying?”

“You’re walking a fine line here.”

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I didn’t ask for any of this.”

“Do you need a moment to gather yourself, Mr. Radford? We need a full accounting of the events.”

Radford reaches yet again for his water, but the glass is empty.

“We need you to take us back to that day, sir. To the events that followed. A year has passed since Pointer 795 exploded. Why have millions of taxpayer dollars been spent on an investigation that has gone nowhere? Don’t we deserve answers? Mr. Radford. Don’t we deserve the truth?”

“You’re asking the wrong questions,” he says.

“What questions should we be asking?”

“My father was a stonemason,” he says. “In many ways, that has been my work too. I reassemble fragments. I work brick by brick. Process is all that matters. I worry only about where the next brick will go. That’s how you get to the end.”

“What happened with Pointer 795? Why did the plane explode over Kansas? How did this investigation go so wrong?”

“I had obligations,” he says. “I had a responsibility to follow the evidence, wherever it took me.”

“And where did it take you, sir?”

“The hardest part is letting go of what you’ve been taught.”

“Mr. Radford, what about the Falling Woman?”

2

(One year earlier)

Charlie Radford was working late again and ignored the vibrating phone in his pocket—which he knew was his wife, Wendy, texting him—so he could keep flying the simulator. He needed to get this report exactly right, even if every additional minute made his wife worry and fret. Radford flew the simulated plane around again, this time lowering a notch of flaps as he came abeam the end of the simulated runway. He cut the throttle, and the propeller slowed as he banked the port wing toward a narrow grass field, carved from a stand of Tennessee pine and hemlock.

Three months earlier, Cessna 417 Yankee X-Ray, a small plane flown by an inexperienced pilot, buzz-sawed the treetops on final approach into the actual William Northern Field. Now Radford was heading up the investigation of the accident, completely routine except for the fact that his immediate supervisor in this case was none other than Dickie Gray himself.

Before the Yankee X-Ray accident, Radford had only passing contact with Dickie Gray, a living legend at the agency, a man who roamed the halls in a faded blue windbreaker with a spiral notepad always tucked in his shirt pocket. Gray had worked all the big ones: TWA 800, Delta 191, USAir 427, the bombing of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. For more than three decades, Gray investigated and solved the most complex aviation accidents, long before Radford knew how to spell the word airplane.

A former fighter pilot, a Vietnam vet, a taciturn whiskey drinker, Dickie Gray was cut from the mold of classic aviators, men with thousand-yard stares and cragged faces. Radford had grown up idolizing men like Dickie Gray, who even looked a bit like Chuck Yeager. There were rumors that the old man had lost his edge, but Radford refused to believe them. Working under Gray’s supervision was the single greatest stroke of good fortune he’d experienced since coming to the NTSB. A well-run investigation would open doors for him. “There are no new ways to crash an airplane,” Gray was fond of saying, advice so important that Radford thought of tattooing it on his arm.

In the simulator, Radford turned toward the airfield, half a mile ahead. The real William Northern Field, seven hundred miles southwest of D.C., consisted of three runways, one of them turf; it was little more than a patch of dirt and grass, where this pilot tried to land. The airfield once existed to train Army Air Corps pilots heading off to bomb Germany in World War II. On the screen, a half dozen simulated taildraggers and biplanes lined the makeshift taxiway in the lengthening shadow of a hangar. The simulator’s graphics were incredible. Radford could hardly tell that he wasn’t in the air. The runway appeared small and treacherous. Flying the approach brought back familiar feelings, thrills long forgotten. He missed being a pilot, missed that fraternity. Flying was all he ever wanted to do. The simulacrum of the small airfield reminded him of a bygone era, when flying was a simpler affair, when no one cared about medical clearances and training modules. In those days, a pilot still cut a dashing figure.

His phone buzzed again. Wendy was struggling of late. He wondered if perhaps pouring himself into the work was a way of avoiding the trouble at home. She worried so much. She catastrophized the simplest things, envisioned car wrecks when he was in traffic, imagined terror attacks when he wasn’t at his desk. Just five more minutes, he thought. He needed to get every detail perfect.

Three hundred feet off the ground, he dropped the starboard wing and pressed the opposite ru

dder, initiating a slip, a maneuver that increased the plane’s drag and accelerated it toward the grass runway. Not a complicated maneuver, as these things went, but flying into a short field with a ten-knot crosswind, the slip challenged Radford’s limited skill set. With every botched approach, he felt a growing kinship with the pilot under investigation, a twenty-year-old flier with three hundred hours of flying time under his belt. At home, in a storage bin, was Radford’s own faded logbook, which contained just less than two hundred hours.

As a boy, when he first became captivated by the elegance and beauty of flight—the sweep of a wing, the pristine lines and curves of a fuselage, the distant rumble of a turboprop—young Charlie Radford would draw airplanes in his notebooks until the 747s he sketched at school bore some fine resemblance to the ones zooming through the sky. Squirreled away in his room like a monk, he built plastic models by the dozens and hung them from his ceiling with fishing line until his bedroom looked like a scaled-down version of the National Air and Space Museum. He internalized the mythology, the science, the history of aviation, as if the very notion of powered flight had been invented solely for him. The pilots who flew planes were his heroes.

The Falling Woman: A Novel

The Falling Woman: A Novel